- Home

- About

-

Interviews

- Penny Arcade

- Bebe Buell

- Richard Christiansen

- Simon Doonan

- Bob Gruen

- Jenn Hampton

- John Holmstrom

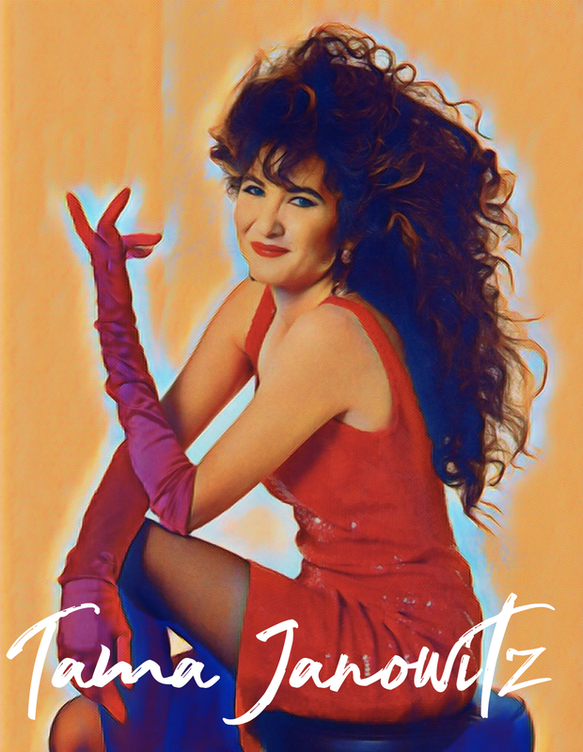

- Tama Janowitz

- Legs McNeil

- Mele Mel & Scorpio

- Matthew Modine

- Jeremiah Moss

- Adam Nelson

- Anton Perich

- Jonny Podell

- Amos Poe

- Kate Pierson

- Parker Posey

- Lady Rizo

- Felipe Rose

- Tony Shafrazi

- Steve Stoute

- Jimmy Webb

- Radio

- Contact

With the publication of her acclaimed short story collection Slaves of New York, Tama Janowitz was crowned the "Lit Girl of New York." Celebrated in rarified literary and social circles, she was hailed, alongside Mark Lindquist, Bret Easton Ellis, and Jay McInerney, as one of the original “Brat Pack” writers—a wave of young minimalist authors whose wry, urbane sensibility captured the zeitgeist of the time, propelling them to the forefront of American culture. Always an original, she left the glamour and glitz of the 1980s behind to be a wife, mother, and poodle wrangler—only to find herself still searching for a sense of purpose. In Scream, her first memoir published in 2016, Janowitz recalls the quirky literary world of young downtown New York in the go-go 1980s and reflects on her life today far away from the city indelible to her work. As in Slaves of New York and A Certain Age, Janowitz turns a critical eye towards life, this time her own, recounting the vagaries of fame and fortune as a writer devoted to her art. Filled with a very real, very personal cast of characters, Scream is an intimate, scorching memoir rife with the humor, insight, and experience of a writer with a surgeon’s eye for detail, and a skill for cutting straight to the strangest parts of life. Boy Scout talked to Janowitz about great ambition, story survival, and finding a plastic cup, preferably without a hole.

Boy Scout: If you arrived in New York City in 2019 filled with great ambition, how might you ascend to your artistic summit?

Tama Janowitz: When I got to NYC, I did not have grand ambition. I have never had grand ambition. I have only had: “help! How am I going to survive?” I was broke and desperate but you could still find a cheap place to stay. Now I don’t think that’s possible. What I did: I got on a bus and took it to the last stop before it turned around.

It left me off in Soho, which was a different place then. I walked a few blocks and saw a crowd of people in front of a building, spilled out onto the street, drinking wine. It was an Art Opening. Kids were making art, selling art, opening galleries. They were friendly! So that’s what I started writing about. Today, if I arrived in New York City and I was rich, I’d write about the wealthy people. If I was a P.R. person, that’s interesting! Or, maybe find a place in East New York, an area in it’s last throes before it will become gentrified. I’d hang out in the remaining, varied neighborhoods in Brooklyn that have different ethnicities and write about the people there. But I don’t know how I’d survive. And although there are millions of stories to write, millions of people to write about, I have lost interest in the city.

A good book is based on a passion on the part of the writer for the subjects. Maybe I would do a Studs Terkel project. Or Barbara Erhenreit, or Jonathan Kozol. Ya know, go live in a homeless shelter. That’s all I could afford, anyway.

Boy Scout: In a time of faltering news platforms, transient facts and generations who opt for digital currency over great literature, how will the stories of those that came before us survive?

Tama Janowitz:I don’t think there were ever that many ‘readers’ in any era. Unless you’re a student, most people, if they do read, are looking for something entertaining, a distraction. But there’s always someone who’s going to tell you, “Right now, I’m reading MOBY DICK”.

Boy Scout: With the eradication of many of New York City’s cultural landmarks through hyper-gentrification, an act that seems to be eroding the soul of many cultural capitals, will our artistic heritages henceforth be confined to yellowing newsprint and the libraries of the past?

Tama Janowitz: Yep. And, the ‘soul of many cultural capitals’ was primarily comprised of immigrant groups – who aren’t allowed here any more – or the poor and disenfranchised, who can’t afford the cultural capitals now anyway.

Boy Scout: The late Harry Dean Stanton believed “Everything is predestined. Nothing is important. Life is an illusion. It’s all a movie. Nobody’s in charge” which is lovingly referred to as his Appreciation of Nothing. Do you have a guiding life philosophy that keeps you on the path?

Tama Janowitz: Harry Dean Stanton was a good actor a lot of the time! but I am suspicious of people who want to be on a stage or in front of a camera as a life’s work. That’s pretty cool, though, that he was ‘predestined’ to be a famous movie star. Harder on those who were ‘predestined’ to work at Walmart and live in a mobile home, right?

Boy Scout: Abraham Lincoln said: “To summon up our better angels.” What are the words you live by?

Tama Janowitz: “Oh my gosh, Tama, you are SUCH a stupid idiot.”

Boy Scout: Anthony Bourdain’s wrenching “Parts Unknown” finale takes place in New York’s lower East Side where a good deal of your history resides.

Tama Janowitz: He was a nice man who went to Vassar and became a cook and then a chef, he took drugs and wanted cooking to be like rock and roll. It was super sad he killed himself, in the middle of getting to live that extraordinary life. But really, he was not so hip as he thought he was. He was quite bourgeois. There’s nothing wrong with that- being bourgeois -- nothing at all. I just find it somewhat affected, to want to prove yourself ‘hip’.

Boy Scout: In that episode, Lydia Lunch says: “People were beautiful, doing things because they had to do it—not because of any other grand idea. Happiness was not the goal; satisfaction was the goal, as it still is. . . . We had to do something because we were burning; our blood was on fire.” Lunch made very clear that in the present day, she wastes no time pining for that bygone time—but Bourdain seemed a little more wistful. As a cultural catalyst, are you ever wistful for an older, grittier New York?

Tama Janowitz: I don’t remember seeing anybody who was ‘burning’ or who had his or her ‘blood on fire’. I didn’t find anybody particularly beautiful either --Just a bunch of hustlers trying to make it, as always. Painting Mickey Mouse or repetitive cartoon squiggles or fake yet sincere mock African Art! Or writing pretty bad stories, or yowling bad poetry over a mike accompanied by screechy bass guitar! Lovely, Lucky Lydia, to have that kind of view, of beauty, passion and sensitivity, all taking place around her! Some people see the glass half-full, etc.

I am just looking around for a plastic cup, preferably without a hole.

I went to Barnard College, Columbia University in the 1970’s. Wow the city was even rougher then than the early ‘80s. It was going bankrupt. It was ‘the panic in Needle Park’ and homeless people everywhere and an old delicatessen on the upper West Side frequented by Isaac Bashevis Singer.

It was great but it was scary. I was sixteen. Right before college I was in The Encampment for Citizenship (you can google this once prestigious program)-- with other kids, only a few ‘white’; they had us working at the Fortune Society, run by former ‘convicts’ (we were told not to ever refer to anyone as an ex-con but I don’t remember how they were to be described; also, never ask anyone what they had been in prison for). We lived in bunk beds inside the Ethical Culture Society building, 64th and CPW, NOT a residence.-- about twenty kids and the counselors. They had us visit the last ‘Chapter of the Black Panthers’ located, then, in Harlem. We were told to say NOTHING or we would all be raped and murdered. The Black Panthers didn’t seem interested in doing so, though!

The head counselor of the Encampment liked to invite the kids to the showers and then make passes at them.

My mother had attended the Encampment in the 1940’s? At that time, the campers stayed at the Fieldston School – where Eleanor Roosevelt spoke, and Paul Robeson sang and they learned about change for the better and how to accomplish it.

By the time I attended, all had changed – Wanda, a tough, angry 16 year old Puerto Rican dyke, with her girlfriend who slept in the bunk above me, with her g.f., yowling all night, threatening to kill me in the day.

Yoshi, a tiny Japanese boy who had a sunken chest, spoke no English but managed to convey Japanese gangsters had beaten him up, resulting in his deformity – what was he doing there?

A couple of Israeli kids – astonished that it did actually rain in the summer here.

The list/descriptions – well, I could go on. But it was rough. At the encampment I met a guy - a nice guy -- I was ‘seeing’ him, though only as a friend – he took me to where he lived – with his grandmother in Jamaica, Queens. Mitchell had a twin; the twin was sent to an Encampment elsewhere, Michigan perhaps? But the twins were split; Mitchell was sent to the NYC Encampment, the same that it was 1973. A sixteen year old white girl in that neighborhood, visiting the home of a fellow ‘encampment citizen’. (watch the Netflix documentary about the murder of Jam Master Jay if you want to see a cleaned up version from what it was like) wandering around there -- Jamaica, Queens, white 16 year old girl, 1973.

I was from Western Massachusetts, out in the country . . .visiting this guy who lived with his grandmother, his sister age twenty, her two year old baby devouring Vaseline out of a jar sitting on the floor while the 1930’s wall paper rippled with waves made from the cockroaches underneath . . . while meanwhile, back in the ‘country’ I had come from, in a land of totally white people. my father was high from dawn until dusk, smoking pot.

Mitchell was murdered a year or two later.

In college, (after the Encampment For Citizenship), a boy took me on a date to Max’s Kansas City’. it was completely empty and closed a short time later. It was still 1973, I was a freshman. . . I went to England on some ‘year abroad’ (goldsmith college) hung out in London 1975-76, went to a part at Andy Logan’s loft where the Sex Pistols (on their second venue) played.

Then . . . back at Barnard, the opening of Studio 54. We (me and some other students – very posh rich New Yorkers who were members of Columbia College’s only remaining fraternity) went on opening night. But it was so mobbed out front and the people were so awful! I looked around and I thought, “Oh my gosh, I don’t want to stand outside on the street with these people, why would I want to be INSIDE with them?” But I went. When I went back to campus, up in Morningside Heights, it was so late I had to take a taxi. I think there was a time when there weren’t subways running at that hour. I was so broke, but I had to get back to the dorm.

I was chatting away with the cab driver and he was, like, ‘come on, ride in the front’ and we stopped at a red light and a man came and shoved a shotgun through the front window of the taxi. The guy asked the cab driver if he wanted to buy it.

Boy Scout: You had said “Writing is almost an act of rebellion on my part.” Where in the world can you find rough, raw, and revolutionary today? Can you share some artists or forms that currently beat your heart?

Tama Janowitz: I never looked for anything rough, raw and revolutionary. Rebellion for me comes from not wanted to present anything with the corners polished; it comes from a need to be honest – honesty as I see the world, even though other people might say, ‘that’s not nice!’ or, ‘she shouldn’t write about those things’, or ‘the people were burning to create!’

Boy Scout: Your artistic works have resulted in seven published novels, one collection of stories and one work of non-fiction. Are you still hungry to explore the bleakly beautiful?

Tama Janowitz: My math is different than yours. I wrote two books of non-fiction, Area Code 212; and Scream. And a children’s book, Hear That? I am not hungry to explore the bleakly beautiful, though, I am tired out. I just want to win the lottery.

Boy Scout: I admire your style of short, blunt, purposely self-evident sentences which, to me, come from a place of hard-worn observation. Can you describe what the commitment of artistic endurance means to you?

Tama Janowitz: It’s horrible. Just horrible. Wouldn’t wish it on anyone. Rather be popular and beloved. Critically well-received. Giving talks and lectures for fifty k. Why stick to some belief that you’ve made up in your own head? Seriously. But I can’t do anything other than what I do.

Boy Scout: Your groundbreaking work Slaves of New York serves as an indelible impression of New York during the height of culture. In that blockbuster, you created a writing style now imbedded in narrative. But fame is fickle, and much like Warhol himself, you had to break from the traps of your earlier success. Does discouragement drive determination? How do you shed a critical voice?

Tama Janowitz: The critical voice is always there, telling me I am no good. You put down words, you have material to re-write, which is where the real work comes in; even though at the time the critical inner voice was busy telling you how terrible those words are and you shouldn’t even bother putting them down.

IF you get the words down, THEN you can start to work. It’s not about waiting for inspiration. There is no muse. You put words on a page, when you have enough words, YOU START THE REVISION. Over and over.

Boy Scout: You moved to upstate New York to provide meaningful caregiving to your dying mother and now reside not far from Ithaca where you have come become quite addicted to horses. City and country living present interesting polarities. What has this relocation taught you?

Tama Janowitz: I stopped enjoying and using the city. The only thing I still liked doing when I was there was walking and exploring new neighborhoods, way out in Brooklyn. I hated the whole ‘scene’. Sometimes I enjoyed ballet, or opera, or getting take-out food from some peculiar place, or finding a discount store or thrift shop. You could go to Coney Island and there were all these Russians with tiny stalls and storage units set up, selling the refuse from other people’s lives. I liked riding the subway and looking at people but the subway's too horrible for even that! Every place got too fancy, too hip for me. Too crowded and too many people vying to have the latest, or see the latest, or go to the latest, or be the latest.

I like being out in the country, except for – up here – around six months of the year when it is freezing cold, grey, snowy, muddy. The other six months are not so bad, except for the heat, droughts, flooding, endless rain and insects. Bad insects. But . . . there are people here in every way as peculiar as those I met and observed in NYC.

Tama Janowitz: When I got to NYC, I did not have grand ambition. I have never had grand ambition. I have only had: “help! How am I going to survive?” I was broke and desperate but you could still find a cheap place to stay. Now I don’t think that’s possible. What I did: I got on a bus and took it to the last stop before it turned around.

It left me off in Soho, which was a different place then. I walked a few blocks and saw a crowd of people in front of a building, spilled out onto the street, drinking wine. It was an Art Opening. Kids were making art, selling art, opening galleries. They were friendly! So that’s what I started writing about. Today, if I arrived in New York City and I was rich, I’d write about the wealthy people. If I was a P.R. person, that’s interesting! Or, maybe find a place in East New York, an area in it’s last throes before it will become gentrified. I’d hang out in the remaining, varied neighborhoods in Brooklyn that have different ethnicities and write about the people there. But I don’t know how I’d survive. And although there are millions of stories to write, millions of people to write about, I have lost interest in the city.

A good book is based on a passion on the part of the writer for the subjects. Maybe I would do a Studs Terkel project. Or Barbara Erhenreit, or Jonathan Kozol. Ya know, go live in a homeless shelter. That’s all I could afford, anyway.

Boy Scout: In a time of faltering news platforms, transient facts and generations who opt for digital currency over great literature, how will the stories of those that came before us survive?

Tama Janowitz:I don’t think there were ever that many ‘readers’ in any era. Unless you’re a student, most people, if they do read, are looking for something entertaining, a distraction. But there’s always someone who’s going to tell you, “Right now, I’m reading MOBY DICK”.

Boy Scout: With the eradication of many of New York City’s cultural landmarks through hyper-gentrification, an act that seems to be eroding the soul of many cultural capitals, will our artistic heritages henceforth be confined to yellowing newsprint and the libraries of the past?

Tama Janowitz: Yep. And, the ‘soul of many cultural capitals’ was primarily comprised of immigrant groups – who aren’t allowed here any more – or the poor and disenfranchised, who can’t afford the cultural capitals now anyway.

Boy Scout: The late Harry Dean Stanton believed “Everything is predestined. Nothing is important. Life is an illusion. It’s all a movie. Nobody’s in charge” which is lovingly referred to as his Appreciation of Nothing. Do you have a guiding life philosophy that keeps you on the path?

Tama Janowitz: Harry Dean Stanton was a good actor a lot of the time! but I am suspicious of people who want to be on a stage or in front of a camera as a life’s work. That’s pretty cool, though, that he was ‘predestined’ to be a famous movie star. Harder on those who were ‘predestined’ to work at Walmart and live in a mobile home, right?

Boy Scout: Abraham Lincoln said: “To summon up our better angels.” What are the words you live by?

Tama Janowitz: “Oh my gosh, Tama, you are SUCH a stupid idiot.”

Boy Scout: Anthony Bourdain’s wrenching “Parts Unknown” finale takes place in New York’s lower East Side where a good deal of your history resides.

Tama Janowitz: He was a nice man who went to Vassar and became a cook and then a chef, he took drugs and wanted cooking to be like rock and roll. It was super sad he killed himself, in the middle of getting to live that extraordinary life. But really, he was not so hip as he thought he was. He was quite bourgeois. There’s nothing wrong with that- being bourgeois -- nothing at all. I just find it somewhat affected, to want to prove yourself ‘hip’.

Boy Scout: In that episode, Lydia Lunch says: “People were beautiful, doing things because they had to do it—not because of any other grand idea. Happiness was not the goal; satisfaction was the goal, as it still is. . . . We had to do something because we were burning; our blood was on fire.” Lunch made very clear that in the present day, she wastes no time pining for that bygone time—but Bourdain seemed a little more wistful. As a cultural catalyst, are you ever wistful for an older, grittier New York?

Tama Janowitz: I don’t remember seeing anybody who was ‘burning’ or who had his or her ‘blood on fire’. I didn’t find anybody particularly beautiful either --Just a bunch of hustlers trying to make it, as always. Painting Mickey Mouse or repetitive cartoon squiggles or fake yet sincere mock African Art! Or writing pretty bad stories, or yowling bad poetry over a mike accompanied by screechy bass guitar! Lovely, Lucky Lydia, to have that kind of view, of beauty, passion and sensitivity, all taking place around her! Some people see the glass half-full, etc.

I am just looking around for a plastic cup, preferably without a hole.

I went to Barnard College, Columbia University in the 1970’s. Wow the city was even rougher then than the early ‘80s. It was going bankrupt. It was ‘the panic in Needle Park’ and homeless people everywhere and an old delicatessen on the upper West Side frequented by Isaac Bashevis Singer.

It was great but it was scary. I was sixteen. Right before college I was in The Encampment for Citizenship (you can google this once prestigious program)-- with other kids, only a few ‘white’; they had us working at the Fortune Society, run by former ‘convicts’ (we were told not to ever refer to anyone as an ex-con but I don’t remember how they were to be described; also, never ask anyone what they had been in prison for). We lived in bunk beds inside the Ethical Culture Society building, 64th and CPW, NOT a residence.-- about twenty kids and the counselors. They had us visit the last ‘Chapter of the Black Panthers’ located, then, in Harlem. We were told to say NOTHING or we would all be raped and murdered. The Black Panthers didn’t seem interested in doing so, though!

The head counselor of the Encampment liked to invite the kids to the showers and then make passes at them.

My mother had attended the Encampment in the 1940’s? At that time, the campers stayed at the Fieldston School – where Eleanor Roosevelt spoke, and Paul Robeson sang and they learned about change for the better and how to accomplish it.

By the time I attended, all had changed – Wanda, a tough, angry 16 year old Puerto Rican dyke, with her girlfriend who slept in the bunk above me, with her g.f., yowling all night, threatening to kill me in the day.

Yoshi, a tiny Japanese boy who had a sunken chest, spoke no English but managed to convey Japanese gangsters had beaten him up, resulting in his deformity – what was he doing there?

A couple of Israeli kids – astonished that it did actually rain in the summer here.

The list/descriptions – well, I could go on. But it was rough. At the encampment I met a guy - a nice guy -- I was ‘seeing’ him, though only as a friend – he took me to where he lived – with his grandmother in Jamaica, Queens. Mitchell had a twin; the twin was sent to an Encampment elsewhere, Michigan perhaps? But the twins were split; Mitchell was sent to the NYC Encampment, the same that it was 1973. A sixteen year old white girl in that neighborhood, visiting the home of a fellow ‘encampment citizen’. (watch the Netflix documentary about the murder of Jam Master Jay if you want to see a cleaned up version from what it was like) wandering around there -- Jamaica, Queens, white 16 year old girl, 1973.

I was from Western Massachusetts, out in the country . . .visiting this guy who lived with his grandmother, his sister age twenty, her two year old baby devouring Vaseline out of a jar sitting on the floor while the 1930’s wall paper rippled with waves made from the cockroaches underneath . . . while meanwhile, back in the ‘country’ I had come from, in a land of totally white people. my father was high from dawn until dusk, smoking pot.

Mitchell was murdered a year or two later.

In college, (after the Encampment For Citizenship), a boy took me on a date to Max’s Kansas City’. it was completely empty and closed a short time later. It was still 1973, I was a freshman. . . I went to England on some ‘year abroad’ (goldsmith college) hung out in London 1975-76, went to a part at Andy Logan’s loft where the Sex Pistols (on their second venue) played.

Then . . . back at Barnard, the opening of Studio 54. We (me and some other students – very posh rich New Yorkers who were members of Columbia College’s only remaining fraternity) went on opening night. But it was so mobbed out front and the people were so awful! I looked around and I thought, “Oh my gosh, I don’t want to stand outside on the street with these people, why would I want to be INSIDE with them?” But I went. When I went back to campus, up in Morningside Heights, it was so late I had to take a taxi. I think there was a time when there weren’t subways running at that hour. I was so broke, but I had to get back to the dorm.

I was chatting away with the cab driver and he was, like, ‘come on, ride in the front’ and we stopped at a red light and a man came and shoved a shotgun through the front window of the taxi. The guy asked the cab driver if he wanted to buy it.

Boy Scout: You had said “Writing is almost an act of rebellion on my part.” Where in the world can you find rough, raw, and revolutionary today? Can you share some artists or forms that currently beat your heart?

Tama Janowitz: I never looked for anything rough, raw and revolutionary. Rebellion for me comes from not wanted to present anything with the corners polished; it comes from a need to be honest – honesty as I see the world, even though other people might say, ‘that’s not nice!’ or, ‘she shouldn’t write about those things’, or ‘the people were burning to create!’

Boy Scout: Your artistic works have resulted in seven published novels, one collection of stories and one work of non-fiction. Are you still hungry to explore the bleakly beautiful?

Tama Janowitz: My math is different than yours. I wrote two books of non-fiction, Area Code 212; and Scream. And a children’s book, Hear That? I am not hungry to explore the bleakly beautiful, though, I am tired out. I just want to win the lottery.

Boy Scout: I admire your style of short, blunt, purposely self-evident sentences which, to me, come from a place of hard-worn observation. Can you describe what the commitment of artistic endurance means to you?

Tama Janowitz: It’s horrible. Just horrible. Wouldn’t wish it on anyone. Rather be popular and beloved. Critically well-received. Giving talks and lectures for fifty k. Why stick to some belief that you’ve made up in your own head? Seriously. But I can’t do anything other than what I do.

Boy Scout: Your groundbreaking work Slaves of New York serves as an indelible impression of New York during the height of culture. In that blockbuster, you created a writing style now imbedded in narrative. But fame is fickle, and much like Warhol himself, you had to break from the traps of your earlier success. Does discouragement drive determination? How do you shed a critical voice?

Tama Janowitz: The critical voice is always there, telling me I am no good. You put down words, you have material to re-write, which is where the real work comes in; even though at the time the critical inner voice was busy telling you how terrible those words are and you shouldn’t even bother putting them down.

IF you get the words down, THEN you can start to work. It’s not about waiting for inspiration. There is no muse. You put words on a page, when you have enough words, YOU START THE REVISION. Over and over.

Boy Scout: You moved to upstate New York to provide meaningful caregiving to your dying mother and now reside not far from Ithaca where you have come become quite addicted to horses. City and country living present interesting polarities. What has this relocation taught you?

Tama Janowitz: I stopped enjoying and using the city. The only thing I still liked doing when I was there was walking and exploring new neighborhoods, way out in Brooklyn. I hated the whole ‘scene’. Sometimes I enjoyed ballet, or opera, or getting take-out food from some peculiar place, or finding a discount store or thrift shop. You could go to Coney Island and there were all these Russians with tiny stalls and storage units set up, selling the refuse from other people’s lives. I liked riding the subway and looking at people but the subway's too horrible for even that! Every place got too fancy, too hip for me. Too crowded and too many people vying to have the latest, or see the latest, or go to the latest, or be the latest.

I like being out in the country, except for – up here – around six months of the year when it is freezing cold, grey, snowy, muddy. The other six months are not so bad, except for the heat, droughts, flooding, endless rain and insects. Bad insects. But . . . there are people here in every way as peculiar as those I met and observed in NYC.